J Mayo Williams – One

in a Million.

Early American

Football and Record Industry Pioneer.

|

Williams in his

college football days. |

Jay Mayo Williams was one of the very

few African American recording company executives before World War II and was

working for several classic labels, among them Paramount, Vocalion,

Brunswick and creating his own influential labels Black Patti and Ebony.

Williams attended the Ivy League College Brown University, where he was

a track star and All-American football player. To say Williams achieved more

than most in many a lifetime would be an understatement, but he managed it in Jim

Crow America.

Jay Mayo “Ink” Williams, who rarely

used his first name or initial, was born on July 25, 1894, in Pine Bluff,

Arkansas. After his father, Daniel Williams, was killed in a railway station

shooting, his mother, Millie, moved the family to Monmouth, Illinois,

where she had originally married her husband in 1885. Mayo Williams grew up in

Monmouth and excelled as a high school athlete, winning a state championship in

the 50-yard dash and taking second place in the 100-yard dash in 1912. He was

part of the Monmouth High Maroons football squad that made it to the

Illinois state championship in 1910. Williams excelled in sports and academically,

he applied and was accepted into Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island in

1916. He continued to perform well on the football field, playing throughout

his college years and making the New York Times All-America third team in 1920. He was also a New England track champion at the 40-yard

distance. Williams's college career was interrupted in 1918 by a stint in the

U.S. Army, where he served as a private. An outstanding scholar and athlete, he

graduated from Brown in 1921 with a major in philosophy.

Williams joined former Brown teammate

Fritz Pollard (First African American NFL player, Coach and Inductee of

the NFL Hall of Fame) along with Paul Robeson (hugely popular singer and

Broadway performer) as members of the Hammond Pros. His playing career

lasted until 1926.

In 1922, Paramount Records, based in Wisconsin just outside of Chicago,

became the second company to market "race" records, following Okeh

from St. Louis. Paramount became famous for its "race" record series

and if any one person could take credit for the success, it was Mayo Williams.

label, headquartered in Port

Washington, Wisconsin. So novel was his position that crowds of children

who had never seen a black person before dogged him from the railroad station

to the label's office, which was headquartered in the Wisconsin Chair

Company's building.

As an educated man dealing largely with artists playing rural music,

Williams, whose musical tastes ran toward more cultured performers like Paul

Robeson, put aside his musical and cultural differences for Paramount. He did

have an appreciation for the blues that he picked up from his mother as a

child, and he felt the style of music was a valuable part of the African-American

community.

By today's standards, it would be unlikely to find a producer who doesn't

socialize with talent. But Williams' "high" social status and

introverted personality may have contributed to his tendency to do just this.

He also maintained that keeping all artists at an equal distance allowed him to

avoid any views of favouritism.

Despite his inexperience, Williams, whose side career in the NFL was never

discovered by Paramount executives, was the most successful "race"

producer of his time. About half of the approximately 40 artists he recorded

for Paramount sold well -around 10,000 copies -- for the company to continue to

record more artists.

Williams established an office on Chicago's South Side, away from the Wisconsin

headquarters of Paramount. His location, in the heart of Chicago's "stroll"

or African-American entertainment district, allowed him to travel to clubs or

cabarets within a few blocks to recruit new talent. He also solicited public

suggestions for talent in African-American newspapers like "The Chicago

Defender."

Williams then talked his way into the

post of manager of the Chicago Music Company, Paramount's publishing

arm. The company paid him poorly and steadfastly refused to give him raises or

promotions. But the situation was ideal from a musical point of view: Williams

rented space at 36th and State Streets on Chicago's South Side, close to the

city's vibrant black entertainment district, and his secretary, Althea

Dickerson, gave him tips about up-and-coming blues acts. He had a good deal

of autonomy from Paramount's white top executives, and from their point of view

(although not that of the performers he signed) he did well: he acquired the

copyrights for much of the music he recorded simply by paying the singer a

token sum (often between five and twenty dollars) and making it clear that the

performer's Paramount recording session depended on his or her going along with

the deal.

Edged out of his position by one of Paramount's

white salesmen, who had actually discovered Jefferson, Williams started his own

label in 1927. It was officially called the Chicago Record Company, but

on the label, he used the name Black Patti, after the black opera

singer M. Sissieretta Jones (known as the Black Patti).

Black Patti 78 rpm releases in the blues, jazz, and gospel genres never sold in

large numbers, but are now among the most prized items in the record collecting

field.

Perhaps most importantly, the label issued the Down Home Boys' "Original

Stack O' Lee Blues." This recording, of which only a handful exist

today, is one of the oldest surviving recordings of the Stagger Lee Blues. A

black folk ballad, the song tells the story of how Stagger Lee shot Billy Lyons

over a Stetson hat. Groups ranging from The Grateful Dead to The Clash

have covered the song, and the owner of the only known Black Patti pressing

still in existence has turned down offers of up to $20,000 for his copy. The record

is proudly owned and jealously guarded by legendary collector Joe Bussard.

Despite the future influence the label would have on music, Black Patti's sales

figures weren't as profitable as hoped, and after just seven months of

operation, the label folded in September of 1927. Today, Black Patti's output

of 55 records has become some of the most sought-after 78s of the period.

Record sales plunged during the Great Depression, and from 1931-1933

Williams returned to football as head coach at the historically black Morehouse

College in Atlanta.

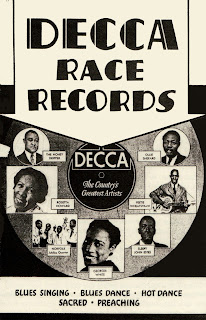

He returned to music in 1934 when the

British label Decca launched its American subsidiary and put Jack

Kapp in charge. Kapp called Williams to New York , signing on as

a talent scout for Decca Records and its legendary 7000 series of

"race" records. By this time, the blues was firmly entrenched in

popular music and only a few labels, including Decca, issued the records

marketed specifically to a black audience.

While employed by Decca, Williams produced the recordings for future gospel

star Mahalia Jackson, as well as former Paramount stars like Trixie

Smith and Blind Joe Taggart.

Williams stepped into the studio with boogie piano acts like Peetie

Wheatstraw and Bumble Bee Slim. He scored a hit with bluesman Kokomo

Arnold's "Milk Cow Blues,"

Upon retiring from Decca in 1946, Williams struck out on his own with Ebony

Records.

The new blues

styles that began to arise in the South and West during and after World War II finally diminished Williams's influence, although he had

one last flash of brilliance when he recorded the young guitarist Muddy

Waters for his Ebony label in the late

1940s before his long association with Chess Records. Williams started

several small labels after the war, eventually selling off rights to some of

his copyrights and returning to Chicago. Williams established a South Side

office for Ebony  |

One of Williams later labels.

|

and continued to run his

one-man company into the 1970s. In all, he spent nearly 50 years in the business.

and continued to work almost until the end

of his life. He died on January 2, 1980.

|

| Williams in his latter years. |

A general underestimation of his influence on the blues tradition has

resulted from his own refusal to assert his own importance in interviews he

gave late in life. According to his biographers, he did, however, tell one

interviewer, "I've been better than 50 percent honest, which in this

business is pretty good."His successes were recognized posthumously in 2004 when the Blues

Foundation acknowledged his contributions to the genre with his induction

into the Blues Hall of Fame.

References

https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/j-mayo-ink-williams-5411/

https://www.encyclopedia.com/education/news-wires-white-papers-and-books/williams-j-mayo

https://www.allaboutbluesmusic.com/j-mayo-williams/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/J._Mayo_Williams

http://ivy50.com/blackhistory/story.aspx?sid=12/26/2006