Len Lawson The Real Life Comic Book Bad Guy Part One

This article is a compilation of several articles previously written on Leonard Lawson all focusing on different aspects of his life, whether it be his time as a popular comic book artist, the censorship in the comic book industry of the era or the resulting criminal cases arising from Lawson terrible deeds. I have arranged and edited them to give a more encompassing story of the man who could’ve been Australia’s greatest comic artist to a man who died in prison of old age.

The articles are listed here for reference.

|

| Len Lawson |

In both M. Night Shyamalan movies Unbreakable (2000) and Glass (2019) Samuel L Jackson plays Elijah Price or Mr. Glass , a superhumanly intelligent mass murderer and comic book theorist with a degenerative disease that makes his bones brittle and makes normal mobility and interaction in society almost impossible. Glass is a supervillain who uses comic book stories to construct intricate scenarios that he plans to the nth degree in complexity. Where this could technically call him a comic book villain Australia lays claim to a real-life comic book killer, once an extremely popular artist and writer Len Lawson.

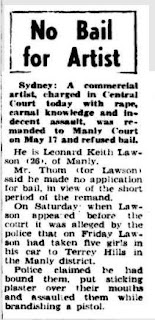

Leonard Keith Lawson went from highly paid successful comic creator and supposedly happily married family man to national disgrace in one crazy act of madness that landed him the death penalty and then released after seven years to commit more acts of an appalling nature that his convictions went on to make him the longest serving inmate in Australian history and eventually dying whilst incarcerated.

EARLY CHILDHOOD

Leonard Keith Lawson was born in 1927 in Wagga Wagga. His parents, Keith and Eileen, were both just 18 when they married and had him. Keith was a local celebrity because he was a talented boxer known as the Wagga Walloper.

Young Leonard — known to all as Len — was a gifted student, topping his classes. But his real talent was art. Len was a natural artist combined with a passion for drawing that his precocious talent showed very early.

In the early 1940s, the Lawson family moved to Manly. There, at age 15, Len scored his first commercial success as a comic book artist when he won a national competition run by artist and publisher Syd Miller, himself famous for co-creating the iconic Chesty Bonds character.

Len’s comic told a war story set in the Pacific and was included in an anthology published by Miller. On the back of that success, Len started studying art in Sydney.

By February 1945, he had published a full-length adventure comic called Peter Jury, which was included in Syd Miller’s Monster Comic publication, whose subtitle was “For Australian Boys”.

“Len is only 17 years of age and has promise of becoming one of Australia’s leading comic artists,” reported Wagga Wagga’s Daily Advertiser.

Len was precocious personally as well as professionally. Just like his own parents, Len was 18 when he married Betty Jamieson, also 18, in September 1946.

The following month, Len got his biggest career break when he wrote and illustrated all the stories in the very first issue of Action Comics, published by H.J. Edwards Pty. Ltd.

Readers were thrilled by the science fiction tale of Spencer Steele, who was exploring the universe in the far-off future of 1956. Then there were the thrills of speed racer Johnnie Star and the adventures of detective Michael Justus.

As a bit of background, the Australian comic market consisted of mostly American imports prior to the 1940s. After the start of World War II, the Australian government banned the import of American comics and Australia was able to develop its own local comic industry. At the conclusion of the war, Australia found itself with a large national debt and a determination to support local businesses. As a result, the Australian government kept the import restrictions in place. This gave Australian comic publishers no competition and a captive audience of comic book readers.

With popular characters like Flash Gordon, the Lone Ranger and Tarzan and their respective comics unavailable there were huge opportunities to be taken of in the local market.

|

| Action Comics where the Lone Avenger was top billing. |

So, by the second issue of Action Comics, a character debuted who’d become Len’s most famous. The Lone Avenger told the story of a masked cowboy named Paul Nicholls, who dressed in a white hat, red mask, green shirt, leather gauntlets, belt, and boots. The Lone Avenger fought crime: first on the range as a wandering hero

Action Comics had been an anthology but The Lone Avenger soon took over the entire book and would continue his crime-fighting run for 13 years. Kids all over Australia, New Zealand and Fiji joined the fan club and bought Lone Avenger toys and outfits.

Len produced other popular characters for Action Comics, including another cowboy dude, this one called The Hooded Rider, and a wild jungle babe in Diana: Queen of the Apes. But The Lone Avenger had the biggest following, selling 70,000 copies per issue.

LEN THE VILLAIN

By the early 1950s, Len was doing brilliantly. He had a successful career, a happy marriage that had produced three children and he was earning £70 a week, which is the equivalent of $2400 a week now. He seemed to have it all. Except something dark and twisted lurked inside Leonard Lawson.

On May 7, 1954, Lawson hired five Sydney models. Two were aged 15, the others were 18, 21 and 23. Lawson wanted them, he said, for a calendar, he proposed to publish. He picked them up from the studio at 9:30am and they stopped in St Leonards to buy some sandwiches, for the day’s supposed picnic ambiance.

Lawson drove them to Terrey Hills and they walked from the car through thick bush. “Of all the beautiful places in Sydney, I don’t know why you had to pick this place to take photographs,” one girl said.

This sunny day soon took a dark turn. “When this calendar comes out, I won’t be here,” Lawson told his young friends gravely. “I have cancer.”

The models were horrified and saddened. Lawson told them he was planning to commit suicide rather than endure an agonising death. “I am thinking about putting a bullet in my brain,” he said.

He took a sawn-off rifle from his backpack (in actual fact a pea-rifle, nothing more than a single shot “slug gun”), loaded it and declared he was going to kill himself there and then. Scared and crying, the girls pleaded with him not to. Lawson abruptly turned the rifle on them, telling them to all lay on their stomachs. He was going to tie them up, he said so they couldn’t stop him from shooting himself. He tied their hands and wrists and used sticking plaster to cover their mouths.

Then his true purpose became clear.

Lawson began removing or cutting off their clothes. Telling them they’d each get a bullet through the head if they resisted, he raped two girls, tried to rape a third and indecently assaulted and intimidated the other two.

“I don’t know why I picked on you decent girls instead of street women,” he said remorsefully when he was done.

Lawson untied his victims, paid them each their £6 fee and drove them to Gordon because one girl wanted to go to a chemist.

It was as if he thought what had happened was no big deal. Once inside the pharmacy, the girl called her parents and the police, who descended and arrested Lawson while he was still sitting in his car outside.

The craziness of Lawson’s actions here is the fact that if any of the women had been more astute, they could have noticed the gun for what it was and could have called Lawson’s bluff and walked away or held him to task for his proposed actions. This is not to suggest the girls were responsible for what happened to them, but their submissive behaviour gave Lawson the confidence to escalate his actions. The regret of his actions so soon after the deeds may indicate that he never intended to go the extremes he did. It however still revealed his hidden psychological problems.

COURTROOM DRAMA

In the days to come, Lawson gave seven confessions. But when the case against him on rape charges was heard from 24th May, he pleaded not guilty.

The girls testified against him at length, providing chilling detail of how he’d manipulated them before unleashing his full savagery.

Not true, Lawson’s lawyer said. The girls had all been willing participants in a “burlesque on the theme of rape”. Testifying, Lawson said he’d had sex with some of his accusers but it had been consensual. He did feel guilty — but only because he’d betrayed his wedding vows.

The jury didn’t need to deliberate for long. The Sun’s front page headline simply screamed “Guilty!” over a portrait of Lawson.

Found guilty on two charges or rape and on a further charge of sexual assault, Justice Clancy passed the death sentence, adding he saw no reason why it should not be carried out, although Lawson would be the first man executed for rape in NSW for 57 years.

Only 17 men had hanged for rape, described as a criminal assault, since 1788. The last man executed for the offence was Charles Hines, on May 21, 1898. Lawson was spared, sentenced instead to 14 years jail when NSW Labor premier Joe Cahill abolished the death penalty in October 1954.